Because I’ve decided to write Biosphere out of order, I wanted to create a list of tips I could follow to keep things stacked in my favor later when editing.

This is not a list of commandments. Think of these as small guardrails that make writing out of order less chaotic and more usable later. You don’t even have to use any of it really since your main focus for writing your first draft (which is essentially just a collection of scenes), is to keep going. So if doing this is in direct competition to that, then ignore it.

Otherwise, here it is:

- Anchor each scene to a question, not a position in the book. Instead of worrying where a scene belongs, try to know why it exists. What question is it answering? What tension is it exploring? Sometimes it’s as simple as, “What does this reveal about their fear?” or “What does this moment cost them?” If you can name the question, the scene has a job, even if you don’t yet know where it lives.

- Label scenes by function rather than chapter number. I’ll often title a scene something like “First major loss”, “Trust breaks,” or “Point of no return,” even if that turns out to be wrong later. Those labels aren’t promises; they’re placeholders. When it comes time to organize, having those functional names makes it much easier to see the story’s shape without rereading everything in full.

- Resist the urge to revise while you’re still discovering. When you write out of order, it’s tempting to keep polishing the same scene because it’s familiar and emotionally satisfying. But over-revising early scenes can trick your brain into feeling productive while avoiding the uncertainty of writing new ones. I try to ask myself, what’s the next exciting thing I can think of that happens in this story? Since you’re writing out of order, it doesn’t have to be the next scene after the current one you’ve written. It can be absolutely anything that comes to your mind first.

- Write scenes at the emotional temperature, not the chronological one. To continue with the thought from the last section: when I’m writing out of order, I’m not asking what comes next in the story. I’m asking what feels emotionally alive right now. What moment is pulling at me? What confrontation, realization, or choice feels urgent? Writing at the emotional temperature keeps the heart of the story intact, even if the timeline is a mess. Chronology can be fixed later. Flat emotional beats are harder to resurrect.

- Keep a running “what I know so far” note, separate from the manuscript. Not an outline, just a living document where you jot down things you’ve realized: who a character really is, what the story seems to be circling around, what the ending might require emotionally. Writing out of order means your understanding evolves in bursts, and capturing those insights keeps you from feeling like you’re constantly starting over.

- Write bookend notes to your scenes. Not necessary but if you already have an approximate idea of where you want the scene, write it in. At the beginning of the scene, write what scenes would need to happen before this scene takes place. At the end of the scene, write what scenes would happen after.

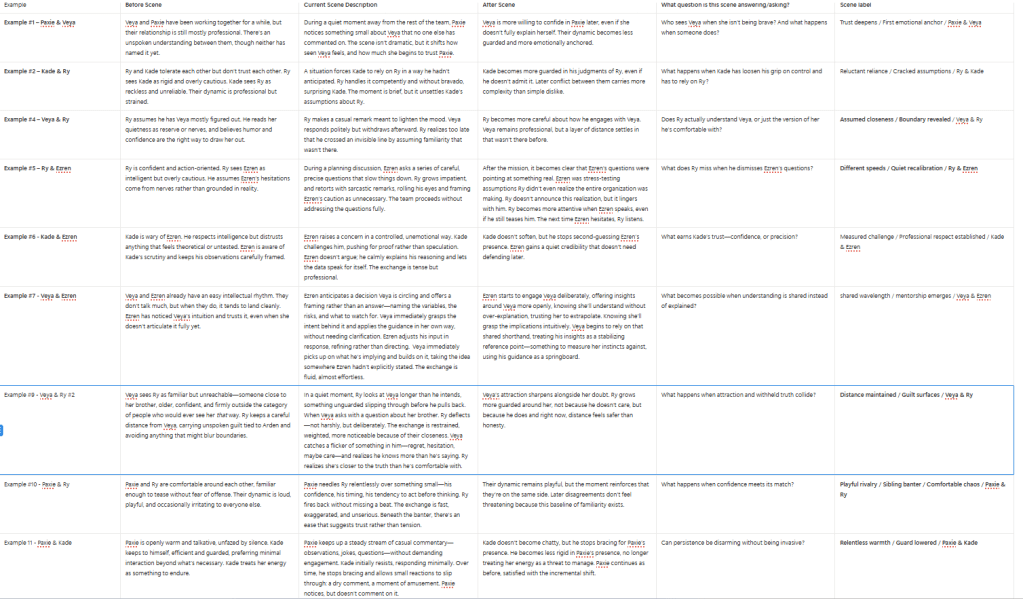

Examples of Bookend Notes for Biosphere

Some examples written out from screenshot above:

Example 1 – Paxie & Veya

- Before Scene:

Veya and Paxie have been working together for a while, but their relationship is still mostly professional. There’s an unspoken understanding between them, though neither has named it yet. - Current Scene Description:

During a quiet moment away from the rest of the team, Paxie notices something small about Veya that no one else has commented on. The scene isn’t dramatic, but it shifts how seen Veya feels, and how much she begins to trust Paxie. - After Scene:

Veya is more willing to confide in Paxie later, even if she doesn’t fully explain herself. Their dynamic becomes less guarded and more emotionally anchored. - What question is this scene answering/asking?

Who sees Veya when she isn’t being brave? And what happens when someone does? - Scene Labels:

Trust deepens / First emotional anchor / Paxie & Veya

Example 2 – Ry & Kade

- Before Scene:

Ry and Kade tolerate each other but don’t trust each other. Ry sees Kade as rigid and overly cautious. Kade sees Ry as reckless and unreliable. Their dynamic is professional but strained. - Scene:

A situation forces Kade to rely on Ry in a way he hadn’t anticipated. Ry handles it competently and without bravado, surprising Kade. The moment is brief, but it unsettles Kade’s assumptions about Ry. - After Scene:

Kade becomes more careful in his judgments of Ry, even if he doesn’t admit it. Later conflict between them carries more complexity than simple dislike. - What question is this scene answering/asking?

What happens when Kade has loosen his grip on absolute control and has to rely on Ry? - Scene Labels:

Reluctant reliance / Cracked assumptions / Ry & Kade

Example 7 – Veya & Ezren

- Before Scene:

Veya and Ezren already have an easy rhythm. They don’t talk much, but when they do, it tends to land cleanly. Ezren has noticed Veya’s intuition and trusts it, even when she doesn’t articulate it fully yet. - Scene:

Ezren anticipates a decision Veya is circling and offers a framing rather than an answer—naming the variables, the risks, and what to watch for. Veya immediately grasps the intent behind it and applies the guidance in her own way, without needing clarification. Ezren adjusts his input in response, refining rather than directing. Veya immediately picks up on what he’s implying and builds on it, taking the idea somewhere Ezren hadn’t explicitly stated. The exchange is fluid, almost effortless. - After Scene:

Ezren starts to engage Veya deliberately, offering insights around Veya more openly, knowing she’ll understand without over-explanation, trusting her to extrapolate and grasp the implications intuitively. Veya begins to rely on that shared shorthand, treating his insights as a stabilizing reference point—something to measure her instincts against, using his guidance as a springboard. - What question is this scene answering/asking?

What becomes possible when understanding is shared instead of explained? - Scene Labels:

shared wavelength / mentorship emerges / Veya & Ezren

Example 11 – Paxie & Kade

(Sorry had to list this one too, love Paxie)

- Before Scene:

Paxie is openly warm and talkative, unfazed by silence. Kade keeps to himself, efficient and guarded, preferring minimal interaction beyond what’s necessary. Kade treats her energy as something to endure. - Scene:

Paxie keeps up a steady stream of casual commentary—observations, jokes, questions—without demanding engagement. Kade initially resists, responding minimally. Over time, he stops bracing and allows small reactions to slip through: a dry comment, a moment of amusement. Paxie notices, but doesn’t comment on it. - After Scene:

Kade doesn’t become chatty, but he stops bracing for Paxie’s presence. He becomes less rigid in Paxie’s presence, no longer treating her energy as a threat to manage. Paxie continues as before, satisfied with the incremental shift. - What question is this scene answering/asking?

Can persistence be disarming without being invasive? - Scene Labels:

Relentless warmth / Guard lowered / Paxie & Kade

Writing Biosphere Out of Order: What This Looks Like in Practice

When I say I’m writing Biosphere out of order, I don’t mean I’m doing it randomly. It just looks that way from the outside.

What’s actually happening is that certain scenes keep surfacing with urgency. Not because I know where they go yet, but because the story clearly wants them written now. Learning to listen to that has been half the experiment.

What a “Pulled” Scene Looks Like in Biosphere

Some scenes arrive already charged. They don’t come with a chapter number attached, but they do come with a feeling. A sense of consequence. A quiet weight.

For example, I might feel pulled toward a moment where a character makes a choice they can’t take back, even if I don’t yet know what led them there. Or a scene where two characters finally say something they’ve been circling for chapters I haven’t written yet. Or a moment of discovery that reframes what the world actually is, even if the reader won’t fully understand its significance until much later.

When those scenes show up, I don’t stop to ask whether it’s “too early” to write them. I write them because they tell me something important about the story. Often, they clarify motivations, stakes, or themes long before the plot catches up.

In Biosphere, these scenes tend to fall into a few loose categories: moments of irreversible choice, moments of emotional fracture, moments of realization about the planet or its rules. I don’t always know how they connect yet, but I know they belong.

How I Label Scenes So Future Me Doesn’t Panic

One thing that helps enormously is not labeling scenes by chapter or order, but by function.

Instead of calling something “Chapter 14,” I’ll think of it as “the first time she understands the cost,” or “trust breaks here,” or “this is the moment everything tilts.” Those labels aren’t permanent. They’re placeholders that tell me why I wrote the scene in the first place.

Later, when I’m ready to organize, those labels will matter more than page numbers. They’ll show me where emotional beats cluster, where the story accelerates, and where something important might be missing.

It also keeps me from overcommitting too early. I’m not locking the scene into a role — I’m just giving it a temporary job description.

The Rule I’m Trying (and Failing) to Follow About Revision

The hardest part of writing out of order is resisting the urge to polish scenes I already love.

With Biosphere, there are a few scenes I could revise endlessly because they feel emotionally satisfying. But I’ve noticed that over-revising early scenes gives me the illusion of progress while quietly avoiding the uncertainty of writing new ones.

Moving Into Draft Two: How I Plan to Organize the Chaos

Draft two is where writing out of order stops feeling like a creative free-for-all and starts feeling like construction.

For me, draft one is a collection of scenes. Draft two is where I decide what kind of story those scenes are actually telling.

Step One: Laying Everything Out Without Editing

When I’m ready to move into draft two, the first thing I’ll do is lay out every scene I’ve written in one place. No fixing. No rewriting. Just seeing what exists.

This is the point where patterns start to show up naturally. I’ll notice where tension spikes, where similar emotional beats repeat, and where large gaps exist. Sometimes I’ll realize I’ve written three versions of the same moment from different angles. Other times, I’ll see that an entire emotional transition is missing.

None of that is failure. It’s information.

Finding the Emotional Spine Before the Plot Spine

Before I worry about exact cause-and-effect logic, I want to understand the emotional flow of Biosphere. Where does hope rise? Where does it fracture? Where does it shift form?

I’m less concerned at this stage with whether every event is perfectly justified and more concerned with whether the emotional progression makes sense. If the emotional arc works, the plot can usually be engineered to support it.

This is where writing out of order actually becomes an advantage. Because the scenes were written from instinct, the emotional truth is often already there — it just needs arranging.

Ordering Scenes for Impact, Not Chronology (Yet)

One thing I’m deliberately allowing in draft two is flexibility around order. Just because a scene could happen earlier doesn’t mean it should.

I’m interested in where scenes land for maximum impact. Where a revelation hurts most. Where a choice feels most irreversible. Where withholding information creates tension instead of confusion.

Chronology matters, but it’s not the first thing I’ll optimize for. Impact comes first. Logic gets its own draft.

Draft Two Is Not About Fixing Everything

This is something I have to remind myself of constantly.

Draft two isn’t where I solve the story. It’s where I organize the story.

Cohesion, transitions, and logic testing all have their own drafts waiting for them. Draft two’s job is simply to take the raw material and give it a shape that can be examined.

Once the shape exists, everything else becomes easier — including tearing it apart later.

Why This Process Feels Right for Biosphere

I think what Biosphere is teaching me is that my biggest enemy isn’t mess — it’s trying to be tidy too early.

Writing out of order lets me protect the heart of the story while it’s still forming. Draft two gives me permission to be analytical without strangling that heart in the process. And later drafts give me space to be ruthless, precise, and logical once the creative work is done.

I don’t know yet if this process will carry me all the way to the end. But for now, it’s keeping the story alive. And that feels like the most important thing.

Mailing List

Welcome to my digital commonplace book. Sign up below to receive articles on all the things I found interesting this week. (I usually write about writing, productivity, self-evolution, with a sprinkle of personal finance here and there.)

Leave a comment